My son is participating in the 40 hour famine this weekend. This is his second year doing the famine, and I am proud of his commitment and effort. It seems fitting, then, that I should blog about hunger and malnutrition today. I’m not going to reiterate the statistics you can easily find on the web. You can look those up if you’re so inclined.

My story is more personal.

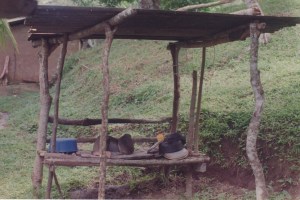

As a Peace Corps Volunteer, I lived in a community of artisans and subsistence farmers in rural Panama. One of my roles in the community was to teach soil conservation and improvement techniques to help farmers get more out of their land and their effort.

Subsistence farming is brutal. Our neighbours in Panama aged quickly, and many bore the scars of their difficult lives. In our village, most people farmed in the morning, then wove baskets and hats or carved soapstone in the afternoon. On market day, they would shoulder huge baskets full of their work and hike three hours up the mountain to sell. By many standards, farmers in our village were rich, because of their craft sales. But rich is relative, and even the most productive villager had precious little money to buy food. Mostly, they ate what they could grow.

Children at birthday parties brought a bag to take food home for their families.

Panama has a four month dry season, during which almost no rain falls at all. By the end of the dry season, the air is like a furnace, and any crops that aren’t watered daily are long gone. New fields are cleared at the end of the dry season, and the brush is burned to make way for new crops. With the first rains, the farmers plant corn, beans, and rice. The new crops need much tending—weeds grow fast in the tropics—and there is much work to be done at the beginning of the rainy season.

Unfortunately, the farmers are doing that work at a time when they have the least amount of food to fuel the effort. Though most people manage to fill their stomachs with something every day, it is rarely enough, and often little more than plain rice. Malnutrition is rife during this lean time of year, and during my time in Panama, it was not uncommon to hear of young adults—generally strong and resilient—dying from simple illnesses because their bodies had no reserves to draw on.

This subtle starvation was nearly invisible to the outside world. Even in the city, the “ricos” had no idea that people starved to death in the surrounding countryside. “But there’s always something to eat in the campo! There can’t possibly be hunger there!”

It is not enough to fill one’s stomach. We all need to eat nutritious and diverse food that provides our bodies all the nutrients they need. Subtle starvation—malnutrition—happens nearby, no matter where you live. There is enough food on earth to feed us all. Let’s all do our part to make sure everyone has enough.